KEITH POTTER

When Ian Gardiner asked me if I’d speak at this conference, I mumbled something about worrying that anything I might produce, given his rather open brief, would come out sounding like the ruminations of a grumpy old man. He replied that “Ruminations of Grumpy Old Men” might be an accurate name for the conference as a whole. Well, we’ll see, won’t we?

What you’ll get, then, for the next half an hour or so from me is my offering as the conference’s (second?) “warm-up man”. For what will probably be my last ever lecture, or conference paper, at Goldsmiths, I think that I have Ian and Tom’s approval to be a little self-indulgent from time to time.

That indulgence will, later on, include a few specific references to Goldsmiths itself and to what we did as a consequence of being here. Goldsmiths, after all, has an honorable tradition of involvement with contemporary music of many kinds, some of them qualifying as “experimental”, “post-minimalist” and so on. When I arrived here to teach in 1976, the pianists John Tilbury and Howard Riley, and the now sadly late electronic-music pioneer Hugh Davies, were all already on the staff; so, at least for a short while, was Cornelius Cardew. And, within a year, I was teaching, among many others, three undergraduates who will be known to many of you – Helen Ottaway (here today), Andrew Poppy (here today), and the now sadly late Jeremy Peyton Jones. I should also add – since this conference involves several musicians who were students at Royal Holloway College (as it was then called) – that the composer, and singer, Brian Dennis had been teaching therefrom the early 1970s; his position in the development of English experimental music helped to make that institution another centre of such activities at the time.

This won’t, then, be a conventional conference paper, with a clear argument and the evidence for it all carefully marshalled. It is, however, divided into four main parts, taking off, in turn from: first, the example I played you at the start of this talk; second, three concerts that took place in 1974 and 1975; third, some contemporary critical reactions to the music of Christopher Hobbs, John White and Steve Reich in the late 1970s and early 1980s; and, lastly, John Cage.

Large parts of the Story of the Seventies are still missing, inevitably. To give just two examples: what about the impact of the social and political concerns of that period on the music of that decade? (I used to teach that the 1970s mirrored the 1930s in being a decade of greater conservatism after a radical one: a reaction against the Sixties, just as the 1930s was a reaction to the 1920s.) What about the impact of popular musics of the 1970s: from the concept album to punk? I hope that I haven’t thrown out too many babies with the bathwater.

What I played you as the first recording, I should explain, is the sound of me sawing a violin in half. That audio example, then, is my first indulgence here.

In 1977, I was invited by Robert Worby (who is here today) to participate in a retrospective of Fluxus activities at the old Air Gallery in the West End. The piece is by Robert Bozzi; it was composed in 1966; and, for reasons I never understood, its title is Choice 8. I’ve not, thus far, been able to find any visual record of this retrospective.

The Fluxus movement, while far from unified as to its intentions, flourished in the 1960s and early 70s, in particular, as a loose-knit artistic movement dedicated, among other things, to the abolition of the status of the professional artist and of art as a professional activity. Though it was often humorous in the way it went about its critique of establishment art and artists, it could sometimes be threatening, even dangerous: to its performers, to its audiences. By 1977, Fluxus had already begun to seem a movement whose time had passed; though I suppose the present international popularity of Marina Abramovic must be some indication that the kinds of things Fluxus stood for are not, in fact, irrelevant in 2024. At Goldsmiths, too, even confining ourselves just to the Music Department, we have had our own ignoble history of Fluxus activities. This dates back to 1963, when John Cale mounted a two-part Fluxus event in the Great Hall that may have been the first public performance of Fluxus compositions in the UK. (Research project, anyone?)

But Robert called his 1977 evening a retrospective. Amidst much else that took place on that merry May evening, I recall Michael Nyman playing La Monte Young’s X for Henry Flynt: Young’s 1960 composition that requires a loud sound to be repeated as exactly as possible, many times. That piece is usually performed as a dense cluster on the piano keyboard. Nyman played a dominant seventh chord on C. And though he did this at the bottom two octaves of the keyboard – thus rather obscuring the consonance of his choice of pitches – I think you can still take this interpretation as, itself, a questioning of Fluxus’s relevance in 1977.

Writing a book on Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians, a composition that was premiered in 1976, I’ve been half (re)living the 1970s during the past few years. It isn’t, necessarily, a healthy pursuit. But it emphasizes what all older folks know: that your formative years, perhaps particularly your first professional years, in your 20s, stack up more memories, more landmarks, more things you subsequently recall as important, than any later period of your life.

That task, like ours today, also makes you realize a potentially important difference between the experience of living through a particular time and coming back to it years later, a point nicely encapsulated by the following quotation:

We inevitably, that is to say, view events as they are being lived through – during which time we have no idea, among other things, of how, and when, they will end – quite differently from the ways in which we might view them subsequently. The Covid pandemic brough this notion home to me with particular force, as it doubtless did to all of us. Applied to our present topic, this causes me, of course, to wonder how those of us who lived through the Seventies might now view the period differently from the way we viewed it then. And also how the view of the Seventies that younger people have will differ from either of those.

Let me now continue this investigation of that decade by taking you up north, to Yorkshire, where I was a student for a while in the mid 1970s. If you had been a resident mouse at York Arts Centre – and as we know, like all churches and former churches, this arts centre must have had its resident rodents – you could, within around a twelve-month slice of this time, have witnessed the following three opportunities to sample the state of contemporary music in the mid-1970s.

First, in October 1974, came Cornelius Cardew, now into his political period and engaged to give a solo piano recital, largely of his own music, that reflected his current preoccupations. Following him, a few months later, were Michael Parsons and Howard Skempton. Now, like him, these two had gone their own way: not, as he did, into political music and activism but, in this period, into writing pieces for percussion duo that reflected ongoing minimalist concerns. Third, and last, in November 1975, Philip Glass turned up at the same venue to play parts of Music in Twelve Parts, a composition completed only the previous year.

Even the audience for the Philip Glass Ensemble struggled, and I’m not sure actually managed, to reach double figures: Philip’s music simply wasn’t nearly as well known here then as was that of Steve Reich. (Robert Worby, again, has been dining out on the story of this York concert for as long as I’ve known him. Which I think was from that November night.)

I love going on about how the musical language, and especially the approach to harmony, of Glass, Reich and many others in the mid-1970s epitomized the shift from minimalism to post-minimalism at this time. But another aspect here, which applies both to the American and the British repertoires involved, is that all these composers were still writing pieces in which the rigour of process was important, perhaps even paramount. I want, now, to use this fact to take us into the only part of my talk that could possibly be termed The Musicology Bit.

In 1975, the attractions of composing with strict processes, or systems as the English experimental composers tended to call them, were still strong for Parsons and Skempton, and for quite a few others such as Dave Smith (also here today). Such processes could be numerical, but also of other kinds. “People processes”, for instance, which involved a group of people working through an action: their own individual ways of doing so resulting in a performance in which, like applying number systems to pitches, the outcomes could not be precisely foreseen. The perfect “experimental act”.

Now what happened if you took this idea of systems and, instead of using, say, pitch material thought up intuitively by the composer, you fed into the system some musical material borrowed from elsewhere? American pieces such as Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain had already done that, in Reich’s case in 1965, of course. Skempton’s Waltz sounds as though he had already got that far in 1970. British composers became especially noted for the extent to which they investigated this approach, including the sometimes idiosyncratic range of borrowed materials on which they drew and the ingenuity they brought to the strategy. Gavin Bryars’s Jesus Blood Never Failed Me Yet, composed in 1971, would be a good example. Bryars’s special shtick for finding a process to give at least a degree of independent life to the unfolding of his musical materials, borrowed or otherwise, became known as “Justification”. (Andrew Hugill, here today, knows all about that aspect of Bryars’s output; including how, and why, he gave it up in 1983-4.) John White, ever alert to the potential of 19th- and early 20th-century music for mid-20th-century compositional purposes, came up with the slogan, “Systems and Sentimentality”. (And then rather spoilt this rather lovely image by adding, “This is the SS of my Reich”.) The basic ploy of applying borrowed musical materials to a process gave Michael Nyman the springboard for a whole career.

In the early to mid 1970s, most of these composers had, though, started to feel that severe self-imposed structural limitations were perhaps not ones they wanted to continue observing in the longer term. Taking your own choice of pitches and putting these through a rigorous number system is one thing. Taking the pitches of other folks – melody, harmony, whatever – and passing these through a rigorous process over which you have no further control, is another. In principle, the results could still be interesting, of course, or at least interesting for some. But such lack of intuitive input on the part of a composer – basically, there were just two decisions involved here: choose the borrowed material, choose the process to run it through – was certainly a kind of extreme as far as composing was concerned. And the results of restricting yourself to just these two acts of composition alone could be horrible. I know. I tried it a few times.

The resulting shift away from the allure of pure process gave rise to the range of styles and aesthetics that many would now characterize as the mature, or at least enduring, periods in the outputs of the composers concerned: everyone from Steve Reich to John White. Or from John Adams to Arvo Pärt, you might say: this minimalist business had fast become an international phenomenon. An added plus here was surely that the capacity sheer repetition had to make familiar musical materials sound unfamiliar – a notable feature of early minimalism, where it gave such music a determinedly radical edge – still obtained, if you handled it carefully, when a hardcore focus on repetition itself had diminished.

The nature of the outcomes varied a lot, of course, according to the composers’ tastes and interests, and their talents. Some retained a significant element of repetition in a minimalist kind of manner. Others – increasingly, one could argue – returned to what we used to call a “common-practice” approach to writing tonal music: with melodies that had accompaniments, perhaps with “proper” bass lines, and engaging with musical forms, as well as textures and harmonies, that were familiar from the practice of earlier Western classical and romantic musics, sometimes from elsewhere too. Dave Smith’s involvement with Albanian music, for instance, as witnessed recently in the revival of his Albanian Summer for saxophone and piano, completed in 1981. If you shift the focus away from Western art music to popular musical forms, then you get Michael Nyman and the starting point for many of the younger generation of composers about whom you’re going to hear more today.

Michael Nyman, “Music”, Studio International, vol. 193 (January/February 1977), pp.6-8

reprinted in Pwyll ap Sion, ed., Michael Nyman: collected writings (Farnham: Ashgate 2013), pp.333-6

All, or any, this, of course, could have had an influence on the way in which the composers who are the intended subjects of the present conference have come to do what they do, and why they did it. In showing you four extracts from reviews from the late 70s and early 80s, the summary points for us go, very briefly, as follows:

In 1977, Michael Nyman is addressing problems that he identifies in the current music of his experimental colleagues, John White and Christopher Hobbs; for Nyman, too, struggling to move away from a rigorous minimalism to find himself as a composer, such issues were becoming urgent. Experimental music is, for him in 1977, now seen as having caused a kind of arrested development in the composers who indulged in it. The skills that it encouraged, if indeed they were skills at all, were not ones that these composers now thought they needed.

Hobbs had, precociously, been engaged in hard-core experimentalism from the time he went to Cardew for composition lessons aged only 16. This meant, Nyman argues, that he had only “found himself as a composer” via a belated attempt to acquire traditional composing skills. But this had led, thus far, at best to quite good pastiche of earlier styles, and at worst to music that was depressing in its reliance on familiar idioms. Even, then, if Hobbs had now found a valid “sentimentality” after his “systems” were left behind, Nyman clearly doesn’t rate the results very highly at this stage.

John White, on the other hand, had already acquired a traditional skillset much earlier on, and was thus much better equipped to write a more narrative kind of tonal music when his need to do this resurfaced. But Nyman also raises the question of whether White is being ironic in his referencing of past idioms: the standard stance for what was to be called post-modernism, but a stance that White himself seemingly rejected.

Later on, in 1981, at the UK premiere of Reich’s Tehillim, Dave Smith is wondering how much of a problem it is when new tonal music eases up on sheer repetition and simultaneously embraces more obviously familiar-sounding musical materials. Even evoking Stravinsky – that past master of kleptomania – is a problem now for Reich, he thinks. But Smith actually considers that sounding like the Andrews Sisters could, in fact, turn out to have its advantages. Note, also, his stern warning to his readers: that the time for “rigid structuralism” is, by the early 80s, now past.

Finally, in 1985, at the UK premiere of Reich’s The Desert Music, Peter Heyworth is firmly convinced that Reich has a big problem. For Heyworth – a hard-line modernist sympathiser for whom the best way forward for late 20th-century composers was to start from scratch, certainly as far as their choice of musical materials was concerned – Reich’s biggest difficulty is another version of what Smith identified: what happens when his music begins to sound like that of much older composers? However clever, Heyworth suggests, a composer might be in manipulating familiar materials in new ways (i.e., here, minimalist repetition), the very act of evocation can only lead swiftly to banality. (Heyworth is the man who, two years later, would stride out of a performance of John Adams’s somewhat Wagnerian Harmonielehre, muttering ”Forgery! Utter forgery!” I know – I was there, too.)

The issues behind these extracts are, of course, considerable ones. How to handle familiar materials, of whatever kind, so as to give them a fresh urgency to speak to “post-experimental”, perhaps “post-modern” listeners? How, in a very old trope in these sorts of discussions, can a composer find “something of their own to say” when treading on such well-worn ground? (“Using a familiar tonal language, but having something individual to say when speaking it” used to be a cliché resorted to by some music critics when they wanted to defend basically conservative kinds of music, of which they approved, against the strictures of modernism, which they hated. But what, exactly – in 1979, or in 2024 – does “something of their own to say” actually mean?) Finally, what role can repetition play today when applied in less hardcore ways than it had been in, say, early Reich and Glass? And when some elements of, say, rock music – an inherently repetitive genre already – are applied to familiar, or to less familiar, melodies and chord sequences?

I want to end by showing a couple of extracts from Peter Greenaway’s 1984 film about John Cage. At this point in my talk, I had intended to ruminate for some while on the significance that Cage’s music and ideas had in the 1970s; and on how, and why, that significance, and that of some of those around him, might be argued to have altered over the last forty or fifty years. This could have helped to justify the inclusion of film extracts that might otherwise appear here as gratuitous and merely indulgent. Unfortunately, however, I have time for no more than a few quick observations that will at least help to bring Cage and Goldsmiths itself together for us.

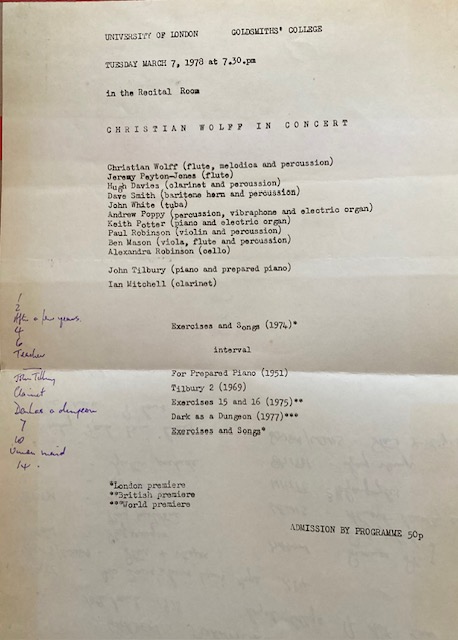

programme for

Christian Wolff in Concert,

Goldsmiths’ College, 7 March 1978

Cage resonated throughout our lives: for me, right through the 1970s and 80s. So, if to a lesser extent, did the work of Morton Feldman and Christian Wolff. While I admit to helping to engineer the concert of Wolff’s music at Goldsmiths in March 1978 that was performed by Wolff himself, by several of those in the English experimental movement and also several Goldsmiths students, I think that there was genuine interest here, stemming partly from the close association that Cardew had long had with Christian: with Wolff’s innovative efforts to find new notations for indeterminate and improvised music; with his principled struggle to reflect his growing left-wing political concerns in his music without, as Cardew had done by this point, rejecting avantgarde and experimental practices altogether.

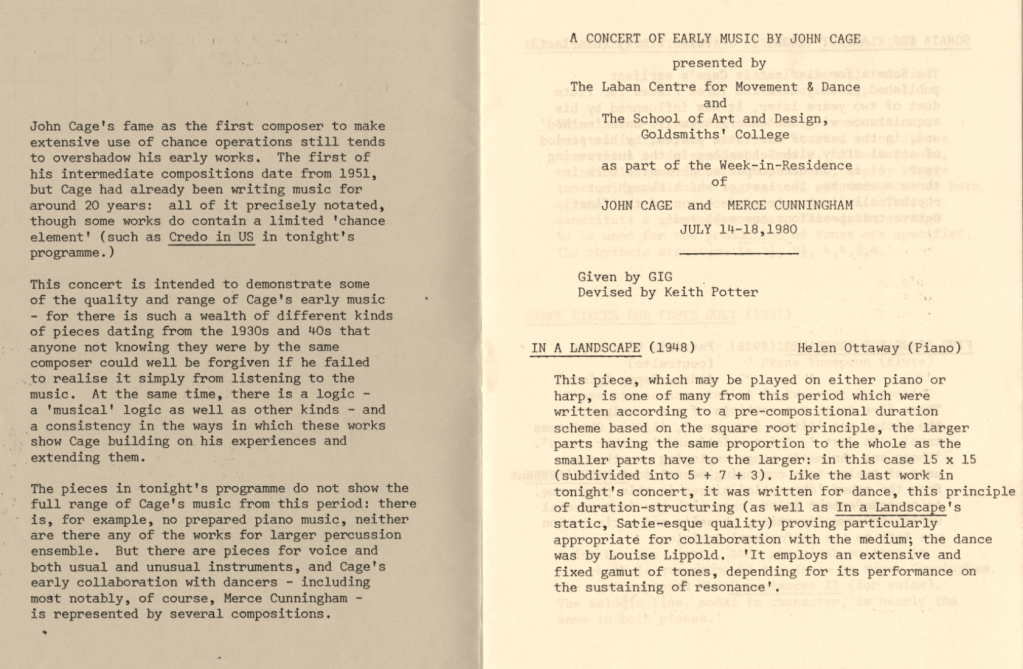

programme for A Concert of Early Music by John Cage, Goldsmiths’ College,

15 July 1980

Cage himself had twice come to Goldsmiths, even before our involvement in the Almeida Festival event in 1982 that led to Greenaway’s film: to lecture in the Great Hall in 1978, just a couple of months after our Wolff concert; and then, much more importantly, as part of the summer school at which Merce Cunningham and Cage both taught for a week. I don’t think I’m alone in considering the five days of music workshops, again in the Great Hall, over which Cage presided, to be one of the greatest weeks of my life.

The usual way to sum up Cage’s influence has been to refer to the “sense of permission” that Cage seemed to give. It wasn’t, then, necessarily a matter of following him into either chance operations or indeterminacy; though some did so, of course. It wasn’t necessarily a matter of moving into improvisation. Some of us well knew that Cage – viewing most improvisation as an expression of personal tastes –denied the validity of improvisation at all. But some of were also aware that improvisation, as well as chance and the rigorous kinds of interpretations of indeterminate works favoured by David Tudor, featured in Cage’s own practice: even before Benjamin Piekut came along later to explain it all to us properly.

So what, I wonder, do the older composers here today, in particular, think that Cage’s impact was on them in the Eighties and Nineties? And what impact do we all think that Cage still has now, in an era in which he is certainly less talked about, and less written about, than he used to be?

A final – and, I promise, short – further word, before I play you the film extracts, about Goldsmiths: with all due apologies for any risk of raining on today’s parade. The ethos here that has enveloped our little community of mavericks – sometimes like-minded, sometimes, I have to declare, not – has never been a perfect model: of collaborative activity, for instance, in which the realities inside our institution have, as perhaps usually happens, never come up to the assumptions made of us by those on the outside. But the Goldsmiths that nurtured so much talent, so much energy, so much innovation – glimpses of which you will shortly see and hear in Greenaway’s film; and, OK, I’ll admit it, the Goldsmiths to which I devoted so much of my life over almost 45 years: that this institution has now trashed, hollowed-out, and desecrated its own music department – making it, as far as I understand things, now pretty much unviable as a going concern and thus ripe for further future culling – all in the name of saving some money. This beggars belief. And cannot, on any grounds, possibly be condoned. Not by me, anyway.

Homily over: let’s watch the film! The first extract here, I hope, helps to explain the second, main one.

[Peter Greenaway, John Cage, from Four American Composers, film for Channel 4 TV, made from performances at the Almeida Festival 1982 (shown on Channel 4 in 1984)]

THANKS TO

Dave Smith (for the audio of ‘Choice 8 ’, and the digitised version of the 1978 Wolff programme; and, well, lots of other things, too!)

Andrew Poppy (for the digitised version of the 1980 Cage programme)

Ian Gardiner (for technical assistance, as well as inviting me to speak today)