IAN GARDINER

This research project emerged out of a conversation with Tom Armstrong as a consequence of a concert to remember the life and work of composer, colleague and friend Jeremy Peyton Jones, where the group he with others founded in 1980, Regular Music, was reconvened to perform some of his early pieces.

Goldsmiths also acquired Jeremy’s archive of scores, parts, sketches, some recordings, which Imogen Burman and I have catalogued and resides in the Special Collections of the library there. The archive reveals a period of prolific compositional and performance activity running roughly from 1980 through to the mid-1990s, with Jeremy writing for Regular Music and for their collaborative projects with theatre companies, theatre and film makers. [Jonathan Parry discusses the early work of the group HERE.] They were one of a number of young, composer-led new music groups and collectives that were formed around this time, set up to play largely their own pieces and arrangements rather than repertoire contemporary music, and in compositional aesthetic, sound and performance, at a distinct tangent from the modernist mainstream in contemporary British art music of the time, connecting more with the legacies of minimalism, US and UK experimental music, pop and jazz.

Although there were precedents for composer-led art music ensembles in Britain during the 60s and 70s – for example, Peter Maxwell Davies’s The Fires of London, or Roger Smalley’s and Tim Souster’s group, Intermodulation – these new groups modelled themselves more on the format of a ‘band’, a collective of composer-performers.

Previous points of reference were the familiar US composer-led ensembles such as Steve Reich and Musicians and the Philip Glass Ensemble, each with its singular instrumentation and sound; and in the UK, the lower-octane register of the groups of idiosyncratic instrumentation assembled by John White, Gavin Bryars, Christopher Hobbs and Dave Smith – the ‘English Experimental’ school of composers, as so labelled and documented in the influential final chapter of Michael Nyman’s Experimental Music – such as the Promenade Theatre Orchestra and the Garden Furniture Music Ensemble. Also, by the late 1970s Nyman’s own rather austere Campiello Band had evolved into the stomping, stridently assertive Michael Nyman Band, whose tightly amplified mix of voice(s), reeds, strings and piano was similarly influential.

[Coincidentally, the Nyman Band was the resident ensemble at a Society for the Promotion of New Music weekend in 1981, for which Jeremy Peyton Jones submitted his sequence of pieces called Purcell Manoeuvres.]

At this time there was also increasing awareness of the Dutch postminimal groups centred around Louis Andriessen, through recordings released by the music publisher Donemus in the late 70s; both the groups Hoketus and Orkest De Volharding played in Britain on Arts Network tours in the early 1980s.

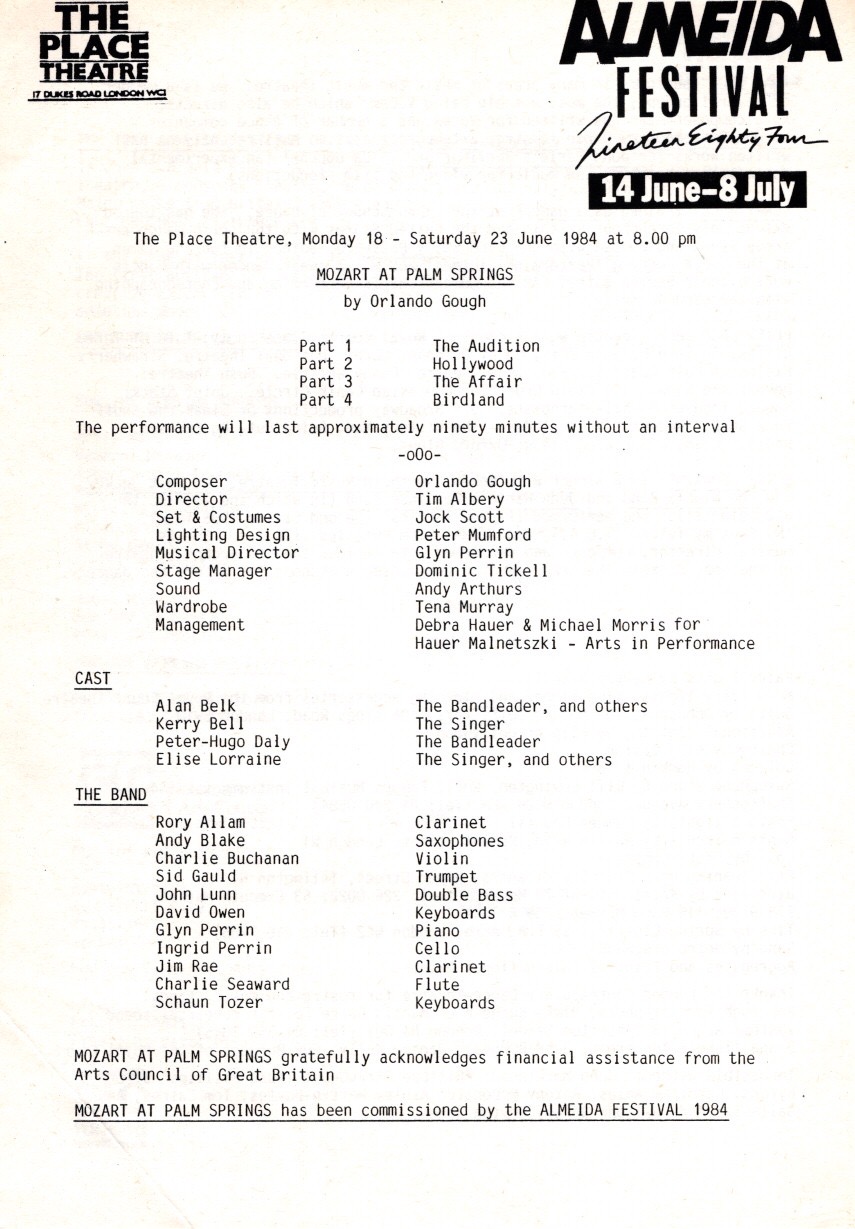

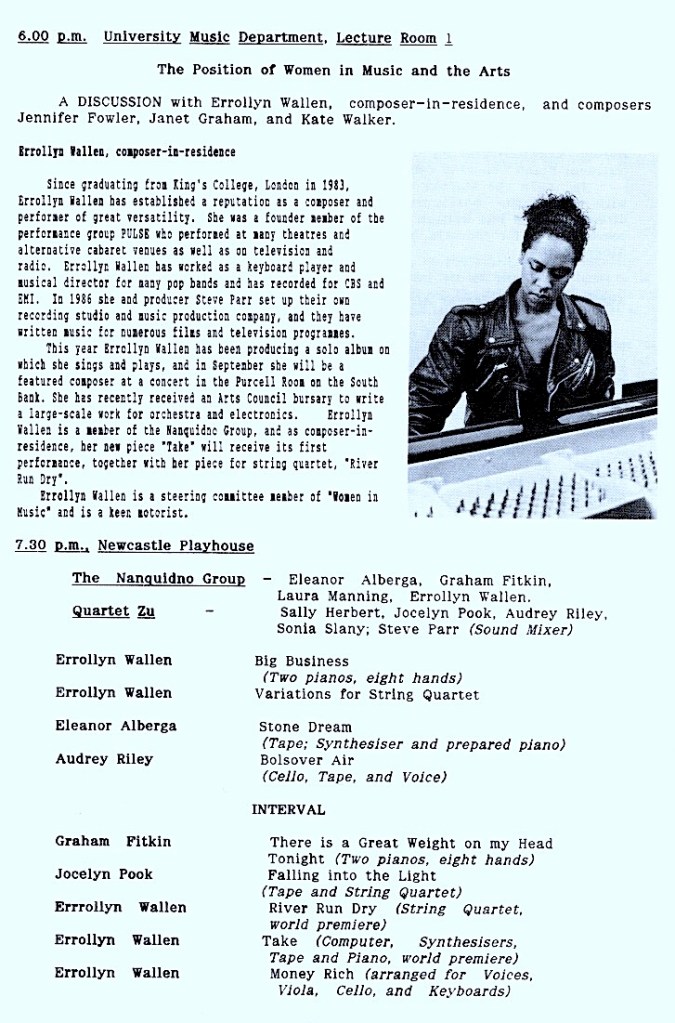

Alongside Regular Music, other British groups of this time included: The Lost Jockey, a big band of eventually almost 30 players – as founder Orlando Gough describes, a group ‘swimming in composers’; its later, sleeker and poppier offshoot, Man Jumping; the mercurial George W Welch (whose origins its founder Andrew Hugill discusses HERE), Graham Fitkin’s Nanquidno Group, Steve Martland’s The Steve Martland Band, and the various ensembles that Andrew Poppy created for his performance and recording projects. All of these were largely based in London.

Clockwise from top left:Lost Jockey / Steve Martland Band /Andrew Poppy Ensemble / Regular Music / Man Jumping / George W Welch

From these we should probably extend outwards to members of those groups who later pursued their own independent work and collaborations. A family tree of performers and composers from this scene would reveal crosscurrents of musicians across groups and across genres, for example, to jazz and improvisational collectives such as Loose Tubes and The Happy End. Although the broad label ‘systems band’ was applied to some of these ensembles, each evidenced a distinctive approach to sound, compositional style and programming.

For some of these bands a connection to popular music was made explicit most obviously through incorporating electric guitar, electric keyboards, and drums playing grooves; and by using close-miced strings, winds and vocals within a uniform and amplified mix. It could also be reflected in a high intensity and forceful performance style, perhaps short on dynamic nuance, and sometimes a little rough-and-ready – as blueprinted in the early recordings by the Nyman Band, for example – and an approach to orchestration that favoured multiple doublings across keyboards and strings/winds/vocals in search of wall-of-sound density. Any changes to orchestration, texture, tempo from section to section tended to be abrupt and terraced, in the manner of a montage jump cut (which became the title of Man Jumping‘s first album). Scoring might also be elastic and reconfigured according to changes in personnel from gig to gig, with pieces undergoing a similar evolution in structure through re-ordering, additional sections or edits. For a Radio 3 session in 1983 (rather oddly, for the programme Jazz in Britain), Lost Jockey overlapped three pieces by different composers as one continuous piece, with the composite title Measuring the Beauty Way.

Across the small number of commercial releases that came out of all this activity, the new digital recording technology lent a hard, flat, compressed quality, much closer to contemporary pop production than classical or jazz recording conventions. These releases were often via independent rock & pop labels – eg. Regular Music on Rough Trade, Andrew Poppy on ZTT, Man Jumping on Cocteau.

Although the mode of performance was often energetic and exuberant, embodying the groove and the cycles of repetition, equally performers might project a ‘No Wave’ pose of cool detachment from their audience. Titles of pieces (and bands) could be playfully non-serious, insouciant, throwaway, oblique . . . (to which I plead guilty also).

In initial discussions Tom Armstrong and I tussled over whether the project should be titled ‘British Postminimalism’ or ‘British Musical Postmodernism’ 1979 – 97. Which Post should we choose? I advocated for the latter title not least as a counterbalance to the period covered in Philip Rupprecht’s estimable analytical survey British Musical Modernism, which takes 1977 as an approximate historical cut-off point for the development of the modernist art music he discusses, a moment when ‘these composers had essentially outgrown the oppositional stance of avant-garde beginnings.’ Lending a label to this music and these groups proved difficult at the time – sometimes they were classified as ‘systems bands‘, Regular Music described itself as a ‘post-Systems band‘, Lost Jockey ‘a post-Systems orchestra‘, one waggish journalist labelled (and libelled) George W. Welch a ‘classico-prankster ensemble‘; by the 1990s this music would became marketed for a time as ‘New Wave‘, then ‘Crossover‘ . . . Nowadays a more common catch-all is ‘post-experimental‘, but that’s a designation that requires extensive qualification around the terms of reference for what is ‘experimental’ (and indeed what is implied by the prefix ‘post-‘). Kyle Gann, in a useful article defining the characteristics of postminimalism, provides a transnational list of composers whose work evidences postminimal materials and processes, including four Brits of this generation – Graham Fitkin, Steve Martland, Jeremy Peyton Jones and Lawrence (sic) Crane.

Kyle Gann, ‘A Technically Definable Stream of Postminimalism, Its Characteristics and Its Meaning’, in Potter, Gann, Ap Sion (eds.): The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music, p.42

In this sense we are designating postminimalism as very broadly defined . . . and we have extended the timeframe of the project into the 1990s, since, by then, it could be argued that postminimal composition had worked its way to the centre via recording labels such as Factory Classical – launched in 1989 according to its founder Anthony H Wilson to ‘wrest the reins of classical music away from middle-class wankers in dinner suits’, the Virgin Venture imprint releasing Michael Nyman’s Peter Greenaway soundtracks, and Decca’s relaunch of the Argo label in 1990, with a strand dedicated to UK and US postminimalism, played by a 2nd generation of young composer/player ensembles such as Icebreaker and Piano Circus. In 1992 BBC Radio 3 inaugurated a further strand in its contemporary music output, to differentiate with the longstanding Music In Our Time series, under the title Midnight Oil, with the first few programmes covering Cage, Martland, David Lang, Gavin Bryars, Gorecki, Orkest De Volharding playing Andriessen, as well as concert performances of more modernist repertoire.

But who or what might be considered postminimal (or postmodern) in British art music composition of this period? Who is within this network of activity, and who sits outside? Perhaps it should also encompass composers who largely performed as soloists – the unclassifiable Chris Newman, for example, whose artwork features in the Midnight Oil flyer above – or groups that played hybrid concerts combining repertoire works alongside pieces from their performers. Or the continuing and evolving work of the resolutely independent and unaligned English Experimental assembly from the previous generation: Bryars, Skempton, White, Hobbs, Smith and others? The formation of independent new music ensembles was also not restricted to those writing in postminimalist/postmodernist styles: several ‘New Complexity’ groups also emerged in this period, programming their own pieces alongside UK premieres of new work from Europe – these include Exposé and Suoraan, to name only two. In his solo piano recitals Michael Finnissy regularly programmed Skempton, White, Crane, Newman alongside his own work.

Perhaps we can stretch our remit in this project to encompass all work that exhibits certain ‘family resemblances’, not just in language and technique, but in approach and position, to paraphrase the much-quoted aphorism from Wittgenstein:

‘A complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: a family resemblance of which the genetic traces are difficult to reduce to common attributes.’

Nevertheless, the London new music scene in this period could be quite oppositional, in a way that might seem odd now to more recent and inclusive generations. Many of the composers cited here I am sure experienced some form of disinterest or dismissal or even hostility towards their work from institutional representatives, critics, gatekeepers . . . and other composers. Here is an extract from the Danish Music Journal in 1992, in which loquacious Danish modernist composer Poul Ruders sees the red mists descend after viewing a publicity shot of Steve Martland on a BBC Symphony Orchestra poster in Clapham South underground station:

“. . . [Martland] is incapable of doing the simplest A to B manoeuvre on a piece of manuscript without falling off the chair he is on, and this is where it gets interesting: the normally quality-conscious BBC Symphony Orchestra is financially in the thick of things (…) and since the orchestra is committed to playing new music, one must resort to launching a talentless Louis Andriessen epigone as a rock star. Martland thinks he is popular with the unemployed, writes (where he can get away with it) against ‘the establishment’, which he calls a collection of assholes, including the people who have helped him. I live in London now, have been coming here regularly for the past 17 years, but this is something new. (…) New music must be easy to understand, either insanely powerful and fast or insanely weak and slow, both preferably for a long, long time AND the most important thing is not the music at all, but the message that the composer has made his trademark (read: scam).”

Underground Thoughts on Art, Dansk Musik Tidsskrift Vol. 67, No.3, pp. 100 – 101 (trans. I.G.)

From what I remember of Steve, he may have been even ruder than Ruders in response. Also what I think eludes Ruders is the concept of a work that may indeed have the intention only to travel from A – B, whilst in musical terms, ‘falling off the chair’. As an unreconstructed postmodernist that sounds quite interesting to me!

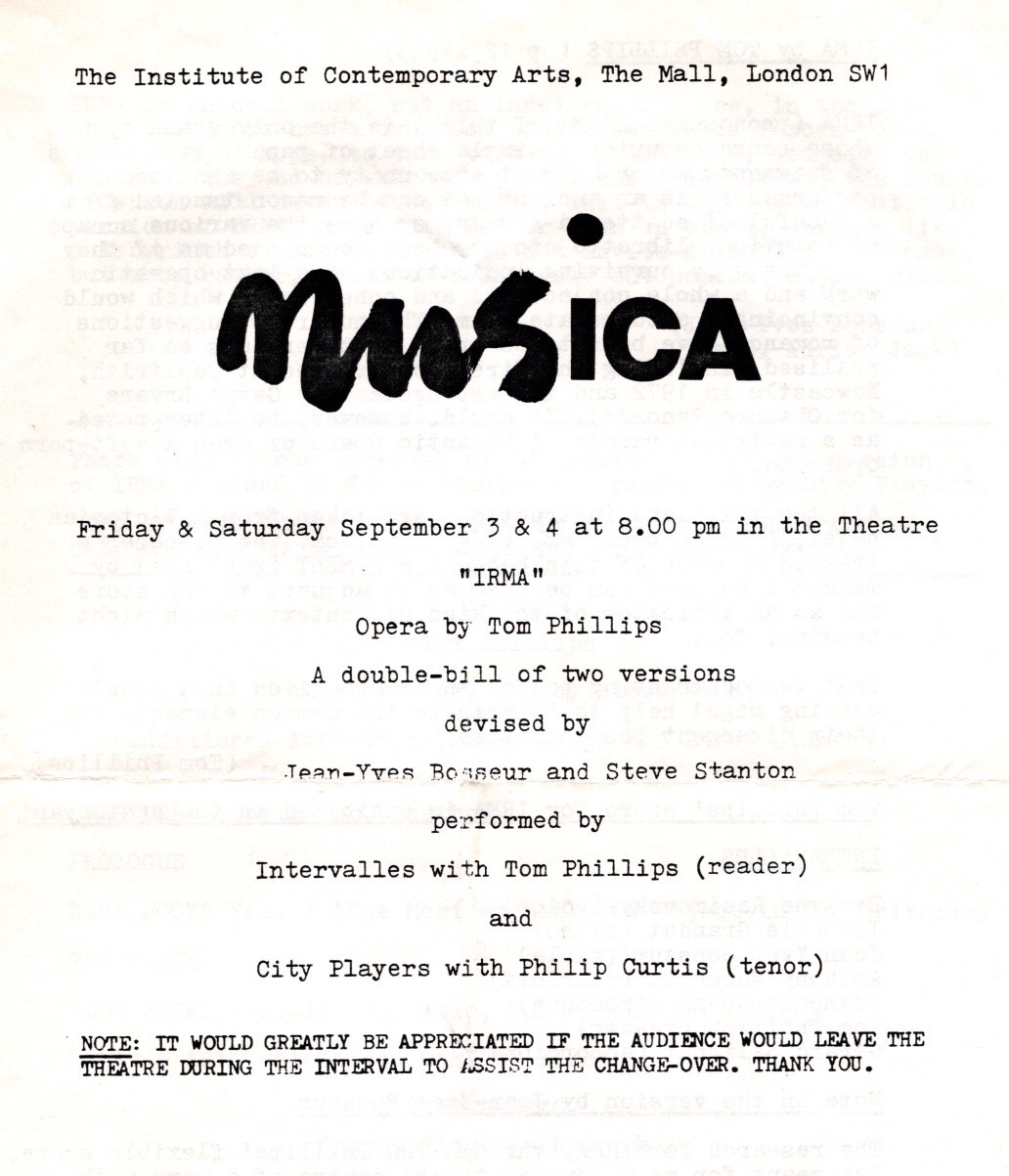

This was an extensive and evolving network of composition, performance and recording, but there were many other actors, including the venues, festivals, promoters and cross-art collaborators that gave a platform for the incubation of new work. A number of London venues formed regular stages for performance, including the ICA, the Africa Centre in Covent Garden, Riverside Studios in Hammersmith, the Place Theatre at the London School of Contemporary Dance in Euston. Smaller groups squeezed into what Keith Potter called ‘the most famous drawing room in the West End’, the British Music Information Centre in Stratford Place, off Oxford St. Patronage was also given by the yearly Almeida Festival of Contemporary Music, which ran at and around the Almeida Theatre in Islington from 1981 to 90; also through Adrian Jack’s inspired and ecumenical curation of the MusICA series at the ICA.

In his article on repetition in live performance of this period, Accommodating the Threat of the Machine: the act of repetition in live performance1, Jeremy Peyton Jones highlights the influence of European performance artists, theatre makers and choreographers on this scene, particularly the physical theatre companies of Pina Bausch, Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker and Wim Wanderkeybus. Several of these music groups formed alliances with British performance makers, most notably Regular Music through large, site-specific performances with Lumière & Son (in collaboration with Hilary Westlake and David Gale), and the Impact Theatre Co-operative (with Pete Brooks and Graeme Miller, among others). Man Jumping and other Lost Jockey offshoots led by Orlando Gough collaborated on dance theatre pieces with the companies Second Stride, London Contemporary Dance Theatre and Shobana Jeyasingh Dance, among others. This ‘unfinished history’ of combined arts and collaborative work is itself a major topic to be researched – Helen Ottaway provides a fascinating glimpse into the combined arts work of the group 3 or 4 Composers HERE.

Clockwise from top left:Lumiere & Son: Panic (music by Jeremy Peyton Jones) / Lumiere & Son: Paradise (music by JPJ) / Wim Vanderkeybus & Ultima Vez: What The Body Does Not Remember / Shobana Jeyasingh Dance: Duets With Automobiles (music by Orlando Gough)

In the ensuing decades all of the composers from these groups developed, refined and, in some cases, radically redefined their compositional practice, but something of the independent, DIY attitude is still evident in their work. Some have progressed to careers with high-profile concert commissions – eg. Errollyn Wallen, Steve Martland, Graham Fitkin – while others established equally prestigious media composition portfolios – John Lunn, Jocelyn Pook, Schaun Tozer. Some still maintain their own live projects, self-publishing and performing – Fitkin again, Poppy, Ottaway, Pook. Some have held established positions in higher education music departments – Peyton Jones, Poppy, Hugill, Crane, Gardiner, et al.

Although a small selection of pieces were recorded for album release, alongside occasional broadcasts through BBC radio sessions, much of the ensemble music in the early period under discussion sits unreleased and unperformed in individual archives. Jeremy Peyton Jones’s archive shows that he recycled several original Regular Music pieces for a variety of reduced or expanded instrumentations, often removing amplification, with structural expansions or contractions, and occasionally integrated them within large-scale performance works. Regular Music’s eponymous 1985 album was re-issued and remastered by Austrian label Klanggalerie in 2019, Man Jumping’s Jumpcut reissued by Emotional Rescue in 2020, and Andrew Poppy released a weighty retrospective of recordings through his Ark Hive of a Live box set on the False Walls label in 2022; but most of the other recordings have not been available for some time (except as YouTube uploads, to relatively small numbers of views).

There is much to explore and re-evaluate in the work and activity of this period, and we hope that this project will open up questions around, inter alia, compositional approaches, aesthetics, aspects of performance, recording and production, cross-art collaborations, archives, and the social and reception history of contemporary music in Britain in the 80s and 90s.

- in Potter, Gann, Ap Sion (eds.), The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music, pp.141-157. Expanded on Gann’s website: https://www.kylegann.com/AshgatePostminimalism.html

↩︎